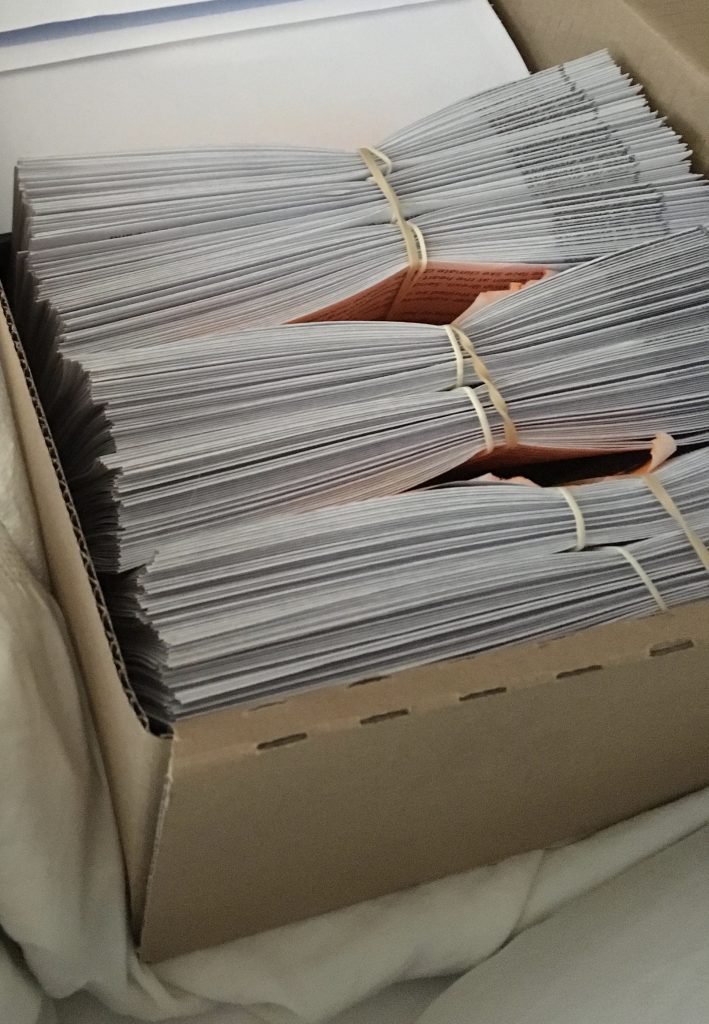

Standing at the doorway smiling, M handed me a cardboard box. Nesting inside were stacks of neatly-folded letters: flocks of origami-birds.

Other hands before mine had folded them, and tied them with bands. Each bundle had a bright orange post-it note with a scribbled code. “They’re ordered by ward and walking-route”, M said. “Best not mix them up”. As if I would. A little calm orderliness felt good in these chaotic times. A little calm ordinariness, cheery, earnest. Leaflets, a cup of strong, builders’ tea and digestive biscuits. Such an English response to the rising waters. Sometimes, I am so terribly English, for a Greek. But then, we share the same patron saint, George, and a dragon’s a dragon, whichever cave you find it in.

Later, I sat on my bed gently pushing the first letters into envelopes that swelled and fluttered in readiness for flight. Their destinations ranged from – sacred to ecclesiastical to secular; St George’s, St Paul’s, Bishopston, Easton, Knowle, and sent me on a map tour of the familiar city in my head. Big green leafy parks, arenas filled with the clattering rush of hard skate wheels on concrete as kids flip and jump and trip over their feet and boards. Hills and traffic and tagging, and unremarkable street after street.

The reason for the box of letters goes back nearly three years to the EU referendum result. Like many I did not sleep well that night, nervously listening to the results coming in on the radio. As the night went on nerves turned to shock, though at the point I dozed off, I was still hopeful that London, stately, scuzzy, pick-n-mix, sugar-rush London, might save the day, in an odd-couple alliance with dour salt-and-water-porridge Scotland.

Instead, I woke on the morning of 24 June 2016 to find that half the country had left the rest of us at home while they embarked on a massive resentment-fuelled bender. None of us knew then how long the hangover would last. It has turned out to be a very long morning after the 70-or so years before. Half the country dressing-up as John Bull in drag every Friday night, chanting meaningless anthems, and drinking themselves silly on imported lager, and gin&tonic before spewing-up bile in the streets. Johnny foreigner looks on with pursed lips and a shake of his head, while the disappointed spouses plot and dream of putting a stop to it all with a mass group intervention.

That morning after, at the gates of my boy’s multi-lingual, multi-coloured school, parents – English, Irish, Hungarian, Algerian, Somalian, West Indian, Polish, American, all of them Bristolian one way or another, were dropping off their children, as usual. Regardless of skin tone, their faces were tighter and paler. A few of us hugged each other but we didn’t have much to say. Disbelief, robbed us of our words, as overnight we found ourselves displaced and disorientated in an unfamiliar new England.

Walking to work after drop off, I did what I do in times of profound crisis: I phoned my dad. “It feels bad, I’ve never felt this was a hostile place before, this is frightening”

“Darling, don’t worry” he said. “It has always been here: English people, they smile at you and are polite. They will come and eat food with you, and be your friend. But really, they think thy are better than you. You are not one of them”, he said.

After work, I went online, and did the other thing I do in times of profound crisis, I bought a kitten from the small-ads. This time from a woman staying with friends and two dogs and three cats in an ex-council flat in Weston-super-Mare. She had just split up, she said. Was looking for a place of her own. She advertised the little tabby as “beautiful part Bengal”. I knew from the photo the mixed-heritage was wishful thinking. But I happily handed over 5 £20 notes, fresh from the cash point, and ignored the white-lie that pushed the price up. I thanked her and drove back home with my new kitten mewing then curling to sleep on the fleece blanket I had bought her in my lunch hour. The estates of Weston were draped with flags of St George hanging limply from bedroom and van windows.

So here we were almost three years later, Minnie, my stout tabby helping me by lounging at the end of the bed and casting a critical eye over my efforts. I tickled her chin and carried on putting euro-election leaflets in envelopes a little more quickly.

Realising half way through that I had not yet read he letter, I unfolded one and the word “Sorry” leapt out. I started to notice the names. In some streets, there was an overabundance of consonants: Grzegorz, Bartlomiej, Agnieszka; In others, an abundance of gods and goddesses: Athena, living on a grey street 10 minutes away. Aphrodite, 20 minutes away. And the spark of recognition, of reaching out, was as bright and warming as a camp fire. And so we carried on, my very own goddess Minnie-Minerva, and I stuffing envelopes. My big high bed, became our arc in the rising waters from where we would send out our fragile little birds.

Minnie chased a few around, hoping to crunch on white-paper bones, then seriously considered sleeping in the box they had come in.

When the waters subside, a bird will come back with a twig in its beak.

e.antoniou 7.6.2019.